Summary

Current Position: US Representative of MN District 5 since 2019

Affiliation: Democrat

Former Position: State Delegate from 2017 – 2019

Other Positions: Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights and International Organizations – House Foreign Affairs Committee

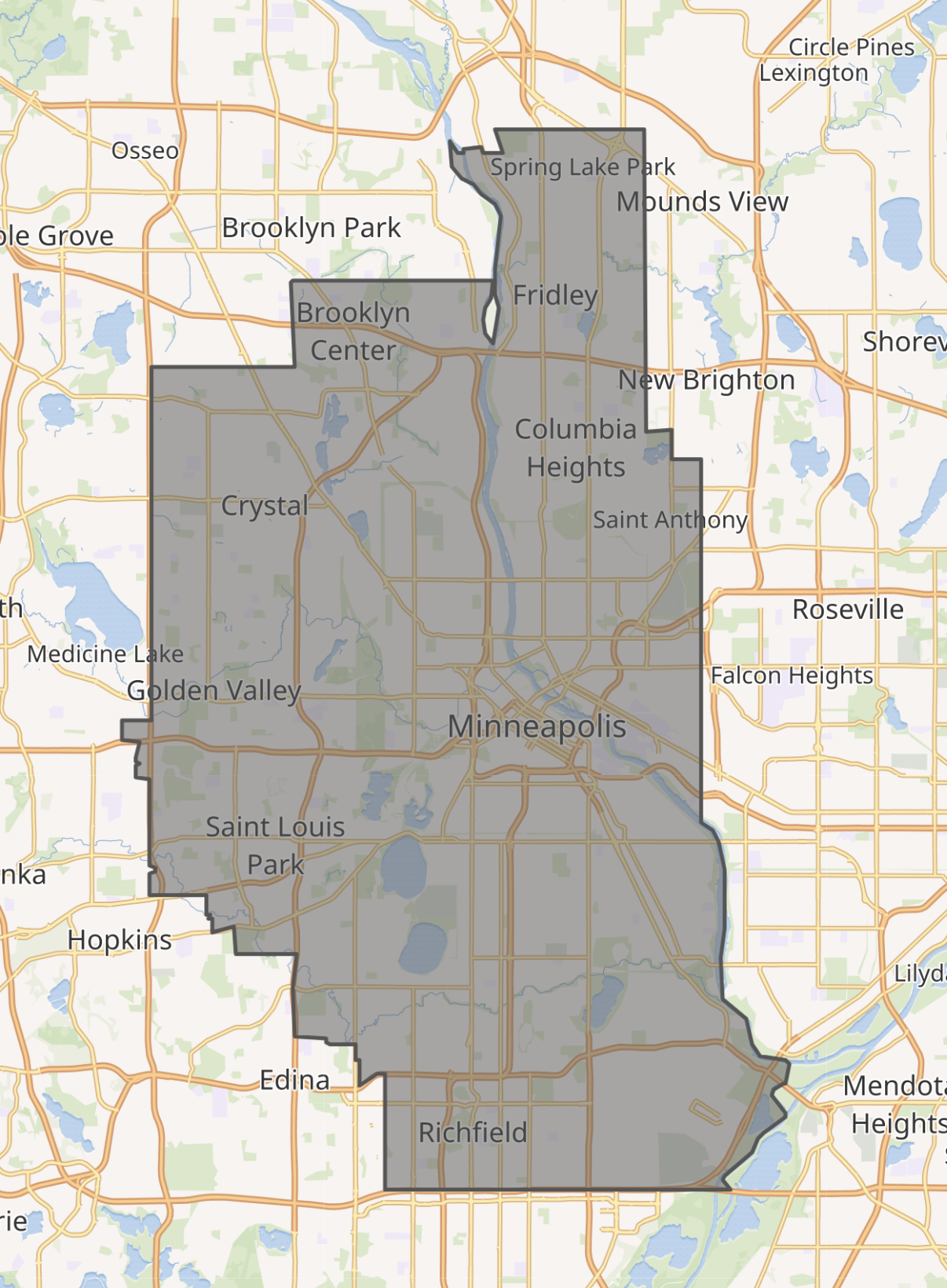

District: eastern Hennepin County, including the entire city of Minneapolis, along with parts of Anoka and Ramsey counties

Upcoming Election:

Omar serves as deputy chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus and has advocated for a $15 minimum wage, universal healthcare, student loan debt forgiveness, the protection of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, and abolishing U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). A frequent critic of Israel, Omar supports the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement and has denounced Israel’s settlement policies and military campaigns in the occupied Palestinian territories,.

Featured Quote:

We urge @POTUS to reopen the U.S. consulate in Jerusalem, reissue State Department & customs guidances to clarify that settlements are inconsistent with international law, & oppose the forced expulsion of Palestinian families in East Jerusalem & throughout Palestinian territory.

Rep. Ilhan Omar shares her experience at border facility

OnAir Post: Ilhan Omar MN-05

News

About

Source: Government page

Rep. Ilhan Omar represents Minnesota’s 5th Congressional District in the U.S. House of Representatives, which includes Minneapolis and surrounding suburbs.

Rep. Ilhan Omar represents Minnesota’s 5th Congressional District in the U.S. House of Representatives, which includes Minneapolis and surrounding suburbs.

An experienced Twin Cities policy analyst, organizer, public speaker and advocate, Rep. Omar was sworn into office in January 2019, making her the first African refugee to become a Member of Congress, the first woman of color to represent Minnesota, and one of the first two Muslim-American women elected to Congress.

As a legislator, Rep. Omar is committed to fighting for the shared values of the 5th District, values that put people at the center of our democracy. She plans to focus on tackling many of the issues that she hears about most from her constituents, like investing in education and freeing students from the shackles of debt; ensuring a fair wage for a hard day’s work; creating a just immigration system and tackling the existential threat of climate change.

Rep. Omar also plans to resist attempts to divide us and push destructive policies that chip away at our rights and freedoms—and to build a more inclusive and compassionate culture, one that will allow our economy to flourish and encourage more Americans to participate in our democracy.

Born in Somalia, Rep. Omar and her family fled the country’s civil war when she was eight. The family spent four years in a refugee camp in Kenya before coming to the United States in 1990s. In 1997, she moved to Minneapolis with her family. As a teenager, Rep. Omar’s grandfather inspired her to get involved in politics. Before running for office, she worked as a community educator at the University of Minnesota, was a Policy Fellow at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs and served as a Senior Policy Aide for the Minneapolis City Council.

In 2016 she was elected as the Minnesota House Representative for District 60B, making her the highest-elected Somali-American public official in the United States and the first Somali-American State Legislator. Rep. Omar served as the Assistant Minority Leader, with assignments to three house committees; Civil Law & Data Practices Policy, Higher Education & Career Readiness Policy and Finance, and State Government Finance.

Personal

Full Name: Ilhan Omar

Gender: Female

Family: Divorced: Ahmed Abdisalan Hirsi; 3 Children; Divorced: Ahmed Nur Said Elmi; Spouse: Tim Mynett

Birth Date: 10/04/1982

Birth Place: Mogadishu, Somalia

Home City: Minneapolis, MN

Religion: Muslim

Source: Vote Smart

Education

BA, Political Science, North Dakota State University, 2011

BS, International Studies, North Dakota State University, 2011

Political Experience

Representative, United States House of Representatives, Minnesota, District 5, 2019-present

Former Member, Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations, United States House of Representatives

Candidate, United States House of Representatives, Minnesota, District 5, 2022

Representative, Minnesota State House of Representatives, District 60B, 2017-2019

Assistant Minority Leader, Minnesota State House of Representatives, 2017-2019

Professional Experience

Director of Policy & Initiatives, Women Organizing Women Network, 2015-present

Policy Fellow, Humphrey School of Public Affairs, University Of Minnesota

Senior Policy Aide, Office of City of Minneapolis Council Member Andrew Johnson, 2013-2015

Campaign Manager, Andrew Johnson for Ward 12, 2013

Child Nutrition Outreach Coordinator, Minnesota Department of Education, 2012-2013

Campaign Manager, Kari Dzeidzik for Minnesota State Senate, 2012

Community Nutrition Educator, University of Minnesota, 2006-2009

Offices

Washington, DC Office

1730 Longworth HOB

Washington, DC 20515

Phone: (202) 225-4755

Minneapolis Office

404 3rd Avenue North

Suite 203

Minneapolis, MN 55401

Phone: (612) 333-1272

Contact

Email: Government

Web Links

Politics

Source: none

Election Results

To learn more, go to this wikipedia section in this post.

Finances

Source: Open Secrets

Committees

Rep. Omar is the Vice-Ranking Member of the House Budget Committee. She also serves on the House Education and Workforce Committee, where she is a member of the Subcommittee on Workforce Protections and Subcommittee on Health, Employment, Labor, Pensions (HELP).

She is the Deputy Chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus and Vice Chair of Medicare For All Caucus. She is a member of the LGBT Equality Caucus, Congressional Black Caucus, Women’s Caucus, Pro-Choice Caucus, Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission, Diabetes Caucus, CBC Taskforce on Black Youth Suicide and Mental Health, Gun Violence Prevention Task Force, Black Maternal Health Caucus, New Americans Caucus, Quiet Skies Caucus, Refugee Caucus, United for Climate and Environmental Justice Congressional Task Force, Unexploded Ordance/Demining Caucus, Public Works and Infrastructure Caucus, Bike Caucus, Black Jewish Caucus, Friends of Norway Caucus, Friends of Sweden Caucus, Hockey Caucus, International Workers Rights Caucus, Labor and Working Families Caucus, Mississippi River Caucus, Sustainable Energy and Environment Coalition, the Career and Technical Education Caucus,Armenian Caucus, Mental Health Caucus, Hunger Caucus, Voting Rights Caucus, Homelessness Caucus, Small Business Caucus, International Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Caucus, Defense Spending Reduction Caucus, Friends of a Free, Stable and Democratic Syria Caucus, the Future of Transportation Caucus, Congressional Labor Caucus, and the ALS Caucus.

New Legislation

Learn more about legislation sponsored and co-sponsored by Representative Omar.

Issues

Source: Government page

More Information

Services

Source: Government page

District

Source: Wikipedia

Minnesota’s 5th congressional district is a geographically small urban and suburban congressional  district in Minnesota. It covers eastern Hennepin County, including the entire city of Minneapolis, along with parts of Anoka and Ramsey counties. Besides Minneapolis, major cities in the district include St. Louis Park, Richfield, Crystal, Robbinsdale, Golden Valley, New Hope, Fridley, and a small portion of Edina.

district in Minnesota. It covers eastern Hennepin County, including the entire city of Minneapolis, along with parts of Anoka and Ramsey counties. Besides Minneapolis, major cities in the district include St. Louis Park, Richfield, Crystal, Robbinsdale, Golden Valley, New Hope, Fridley, and a small portion of Edina.

It was created in 1883, and was nicknamed the “Bloody Fifth” on account of its first election. The contest between Knute Nelson and Charles F. Kindred involved graft, intimidation, and election fraud at every turn. The Republican convention on July 12 in Detroit Lakes was compared to the historic Battle of the Boyne in Ireland. One hundred and fifty delegates fought over eighty seats. After a scuffle in the main conference center, the Kindred and Nelson campaigns nominated each of their candidates.

The district is strongly Democratic, with a Cook Partisan Voting Index (CPVI) of D+30 — by far the most Democratic district in the state. The 5th is also the most Democratic district in the Upper Midwest. The Minnesota Democratic–Farmer–Labor Party (DFL) has held the seat without interruption since 1963, and the Republicans have not tallied more than 40 percent of the vote in almost half a century.

The district is represented by Ilhan Omar, who is the first Somali–American to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives, and the first woman of color to represent Minnesota in that chamber. Omar, also an American Muslim, succeeded Keith Ellison, the first American Muslim to serve in Congress, after he was elected Minnesota Attorney General.

Wikipedia

Contents

(Top)

1

Early life and education

2

Early career

3

Minnesota House of Representatives

4

U.S. House of Representatives

5

Political positions

6

Death threats and harassment

7

Electoral history

8

Awards and honors

9

Media appearances

10

Personal life

11

See also

12

Notes

13

References

14

Further reading

15

External links

Ilhan Abdullahi Omar (born October 4, 1982) is an American politician serving as the U.S. representative for Minnesota’s 5th congressional district since 2019. She is a member of the Democratic Party. Before her election to Congress, Omar served in the Minnesota House of Representatives from 2017 to 2019, representing part of Minneapolis. Her congressional district includes all of Minneapolis and some of its first-ring suburbs.

Omar serves as deputy chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus and has advocated for a $15 minimum wage, universal healthcare, student loan debt forgiveness, the protection of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, and abolishing U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). A frequent critic of Israel, Omar supports the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement and has denounced Israel’s settlement policies and military campaigns in the occupied Palestinian territories, as well as the influence of pro-Israel lobbies in American politics.[2][3][4] In February 2023, the Republican-controlled House voted to remove Omar from her seat on the Foreign Affairs Committee, citing past comments she had made about Israel and concerns over her objectivity.[5]

Omar is the first Somali American in the United States Congress and the first woman of color to represent Minnesota.[6] She is also one of the first two Muslim women (along with Rashida Tlaib) to serve in Congress.[7][8] Her political opponents, including Donald Trump, have made derogatory comments related to her background. She has also received several death threats.[9][10]

Early life and education

Ilhan Abdullahi Omar was born in Mogadishu, Somalia, on October 4, 1982,[11][12] and spent her early years in Baidoa, in southern Somalia.[13][14] She was the youngest of seven siblings. Her father is Nur Omar Mohamed, an ethnic Somali from the Osman Mohamud sub-clan of Majeerteen,[15] a clan in Northeastern Somalia.[16] He was a colonel in the Somali Army under Siad Barre, and served in the Ogaden War (1977–78). He also worked as a teacher trainer.[17][18]

Omar’s mother, Fadhuma Abukar Haji Hussein, an ethnic Benadiri, died when Omar was two.[19][20][21][22] Omar was raised by her father and grandfather, who were moderate Sunni Muslims opposed to the rigid Wahhabi interpretation of Islam.[23][24] Her grandfather Abukar was the director of Somalia’s National Marine Transport, and some of Omar’s uncles and aunts also worked as civil servants and educators.[18] She and her family fled Somalia to escape the Somali Civil War and spent four years in a Dadaab refugee camp in Garissa County, Kenya.[25][26][27]

Omar’s family secured asylum in the U.S. and arrived in New York in 1995,[28][29] then lived for a time in Arlington, Virginia,[21] before moving to and settling in Minneapolis,[21] where her father worked first as a taxi driver and later for the post office.[21] Her father and grandfather emphasized the importance of democracy during her upbringing, and at age 14 she accompanied her grandfather to caucus meetings, serving as his interpreter.[24][30] She has spoken about school bullying she endured during her time in Virginia, stimulated by her distinctive Somali appearance and wearing of the hijab. She recalls gum being pressed into her hijab, being pushed down stairs, and physical taunts while she was changing for gym class.[21] Omar remembers her father’s reaction to these incidents: “They are doing something to you because they feel threatened in some way by your existence.”[21] Omar became a U.S. citizen in 2000 when she was 17 years old.[31][21]

Omar attended Thomas Edison High School, from which she graduated in 2001, and volunteered as a student organizer.[32] She graduated from North Dakota State University in 2011 with a bachelor’s degree, majoring in political science and international studies.[33][30] Omar was a policy fellow at the University of Minnesota‘s Humphrey School of Public Affairs.[34][35][36]

Early career

Omar began her professional career as a community nutrition educator at the University of Minnesota, working in that capacity from 2006 to 2009 in the greater Minneapolis–Saint Paul area. In 2012, she served as campaign manager for Kari Dziedzic‘s reelection campaign for the Minnesota State Senate. Between 2012 and 2013, she was a child nutrition outreach coordinator at the Minnesota Department of Education.[37]

In 2013, Omar managed Andrew Johnson‘s campaign for Minneapolis City Council. After Johnson was elected, she served as his senior policy aide from 2013 to 2015.[34] In February 2014, during a contentious precinct caucus that turned violent, Omar was attacked by five people and injured.[18] According to MinnPost, the day before the caucus, Minneapolis city council member Abdi Warsame had told Johnson to warn Omar not to attend the meeting.[38]

As of September 2015, Omar was the Director of Policy Initiatives of the Women Organizing Women Network, advocating for women from East Africa to take on civic and political leadership roles.[34] In September 2018, Jeff Cirillo of Roll Call called her a “progressive rising star”.[39]

Minnesota House of Representatives

Elections

In 2016, Omar ran on the Democratic–Farmer–Labor (DFL) ticket for the Minnesota House of Representatives in District 60B, which includes part of northeast Minneapolis. On August 9, Omar defeated Mohamud Noor and incumbent Phyllis Kahn in the DFL primary.[40] Her chief opponent in the general election was Republican nominee Abdimalik Askar, another activist in the Somali-American community. In late August, Askar announced his withdrawal from the campaign.[41] In November, Omar won the general election, becoming the first Somali-American legislator in the United States.[42] Her term began on January 3, 2017.[43]

Tenure and activity

During her tenure as state representative for District 60B, Omar was an assistant minority leader for the DFL caucus.[44][45] She authored 38 bills during the 2017–2018 legislative session.[46][47]

Committee assignments

- Civil Law & Data Practices Policy

- Higher Education & Career Readiness Policy & Finance

- State Government Finance[48]

Campaign finance investigations

In 2018, Republican state representative Steve Drazkowski publicly accused Omar of campaign finance violations,[12] claiming that she used campaign funds to pay a divorce lawyer, and that her acceptance of speaking fees from public colleges violated Minnesota House rules. Omar responded that the attorney’s fees were not personal but campaign-related; she offered to return the speaking fees.[49][50] Drazkowski later accused Omar of improperly using campaign funds for personal travel to Estonia and locations in the U.S.[12][51][31]

Omar’s campaign dismissed the accusations as politically motivated and accused Drazkowski of using public funds to harass a Muslim candidate.[31][29] In response to an editorial in the Minneapolis Star Tribune arguing that Omar should be more transparent about her use of campaign funds, she said: “these people are part of systems that have historically been disturbingly motivated to silence, discredit and dehumanize influencers who threaten the establishment.”[31]

In June 2019, Minnesota campaign finance officials ruled that Omar had to pay back $3,500 that she had spent on out-of-state travel and tax filing in violation of state law, plus a $500 fine.[52] The Campaign Finance Board’s investigation also found that, in 2014 and 2015, Omar had jointly filed taxes with a man to whom she was not legally married. Unlike some states, Minnesota does not recognize common-law marriage, and so such a joint filing is not legally permitted. But experts have said that if the taxpayer files a correction within three years, as Omar’s attorney and accountants did in 2016, then there are normally no further consequences, and the Internal Revenue Service is unlikely to pursue punitive measures unless there is a large discrepancy or fraudulent intent. In response to the AP‘s request for comment, her campaign sent a statement saying, “all of Rep. Omar’s tax filings are fully compliant with all applicable tax law.”[53][54][55]

U.S. House of Representatives

Elections

2018

On June 5, 2018, Omar filed to run for the United States House of Representatives from Minnesota’s 5th congressional district after six-term incumbent Keith Ellison announced he would not seek reelection.[56] On June 17, she was endorsed by the Minnesota Democratic–Farmer–Labor Party after two rounds of voting.[57] Omar won the August 14 primary with 48.2% of the vote.[58]

The 5th district is the most Democratic district in Minnesota and the Upper Midwest (it has a Cook Partisan Voting Index of D+26) and the DFL has held it since 1963. Omar faced health care worker and conservative activist Jennifer Zielinski in the November 6 general election[59] and won with 78.0% of the vote, becoming the first Somali American elected to the U.S. Congress, the first woman of color to serve as a U.S. representative from Minnesota,[7] and (alongside former Michigan state representative Rashida Tlaib) one of the first Muslim women elected to the Congress.[60][61][62]

Omar received the largest percentage of the vote of any female candidate for U.S. House in state history,[63] as well as the largest percentage for a non-incumbent U.S. House candidate (excluding those running against only minor-party candidates).[63] She was sworn in on a copy of the Quran owned by her grandfather.[64][65]

2020

Omar won the Democratic nomination in the August 11 Democratic primary, in which she faced four opponents. The strongest was mediation lawyer Antone Melton-Meaux, who raised $3.2 million in April–June 2020, compared to about $500,000 by Omar; much of Melton-Meaux’s funding came from pro-Israel groups.[66][67] Melton-Meaux was also endorsed by Minnesota’s largest newspaper, The Star Tribune.[68] This led some analysts to predict a close race,[69] but Omar received 57.4% of the vote to Melton-Meaux’s 39.2%.[70][71]

She defeated Republican Lacy Johnson and Legal Marijuana Now Party candidate Michael Moore in the November 3 general election, with 64.3% of the vote to Johnson’s 25.8% and Moore’s 9.5%.[72] Omar’s margin of victory was 24 points less than Biden’s in the district, the highest underperformance of any Democrat in the nation, which Nathaniel Rakich of FiveThirtyEight attributed to increased Republican spending and Moore’s progressive pro-marijuana campaign.[73]

2022

In the August 9 Democratic primary, Omar faced former Minneapolis councilman Don Samuels and three other opponents.[74] The campaign primarily focused on crime and Omar’s effectiveness in office.[75] Omar’s campaign outspent Samuels’s by $2.1 million to $800,000; Samuels ran television ads while Omar’s campaign did not.[75] Omar won the primary with 50.3% of the vote to Samuels’s 48.2%, a margin of fewer than 2,500 votes.[76]

2024

Omar won the August 13 Democratic primary with 56% of the vote against Don Samuels, whom she defeated in the 2022 primary, Tim Peterson, and Sarah Gad.[77][78] She was reelected to a fourth term with 75.3% of the vote.[79]

Tenure

Following Omar’s election, the ban on head coverings in the U.S. House was modified, and Omar became the first woman to wear a hijab on the House floor.[21] She is a member of the informal group known as “The Squad“, whose members form a unified front to push for progressive changes such as the Green New Deal and Medicare for All. The other members of the Squad are Ayanna Pressley, Rashida Tlaib, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.[80]

Brian Stelter of CNN Business found that from January to July 2019 Omar was mentioned about twice as often on Fox News as on CNN and MSNBC, and about six times as often as James Clyburn, a Democratic House leader.[81] A CBS News and YouGov poll of almost 2,100 U.S. adults conducted from July 17 to 19 found that Republican respondents were more aware of Omar than Democratic respondents. Omar has very unfavorable ratings among Republican respondents and favorable ratings among Democratic respondents. The same is true of the other members of the Squad.[82]

On September 10, 2025, Omar condemned the assassination of Charlie Kirk, saying, “political violence is completely unacceptable and indefensible.”[83] She called conservatives who blamed the left for the shooting “full of shit”[84] and reposted a video calling Kirk a “stochastic terrorist” who “with his last dying words … was spewing racist dogwhistles”. This led to two Republican efforts to strip Omar of her committee assignments.[85] One of them, led by Representative Nancy Mace, failed on September 17, 2025, with four Republicans joining all Democrats to kill the measure.[86]

Legislation

In July 2019, Omar introduced a resolution co-sponsored by Rashida Tlaib and Georgia representative John Lewis stating that “all Americans have the right to participate in boycotts in pursuit of civil and human rights at home and abroad, as protected by the First Amendment to the Constitution”. The resolution “opposes unconstitutional legislative efforts to limit the use of boycotts to further civil rights at home and abroad”, and “urges Congress, States, and civil rights leaders from all communities to endeavor to preserve the freedom of advocacy for all by opposing anti-boycott resolutions and legislation”.[87] In the same month, Omar was one of 17 members of Congress to vote against a House resolution condemning the BDS movement.[88]

On January 7, 2021, Omar led a group of 13 House members introducing articles of impeachment against Trump on charges of high crimes and misdemeanors.[89] The charges are related to Trump‘s alleged interference in the 2020 presidential election in Georgia and incitement of the attack at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., by his supporters, which occurred during the certification of electoral votes in the 2020 presidential election that affirmed Joe Biden‘s victory.[90][91]

In 2022, Omar urged the renewal of the MEALS Act, which provided free meals to 20-30 million children amid rising prices due to the Russo-Ukrainian war.[92] Additionally, her sponsored piece of legislation, a bill to rename the central Minneapolis post office after former congressman Martin Olav Sabo, became law.[93]

Committee assignments

For the 119th Congress:[94]

Caucuses

- Congressional Progressive Caucus deputy chair[95]

- Black Maternal Health Caucus[96]

- Congressional Black Caucus[97]

- Congressional Caucus for the Equal Rights Amendment[98]

- Congressional Equality Caucus[99]

2021 U.S. Capitol attack

After the 2021 United States Capitol attack, Omar said the experience was traumatizing. She said she began to fear for her life when the evacuation began, and as she was being escorted to a secure area, she telephoned her children’s father to “make sure he would continue to tell my children that I loved them if I didn’t make it out.” Omar added: “The face of the Capitol will forever be changed. They didn’t succeed in stopping the functions of democracy, but I do believe they succeeded in ending the openness of our democracy.”[100]

Financial disclosures

Omar reported a negative net worth when initially elected in 2018.[101] She reported in her 2024 financial filing that she and her husband, Tim Mynett, had a household net worth between $6 million and $30 million at the end of 2024.[102] Mynett and Omar’s wealth derives almost entirely from his ownership stake in two companies, a California-based winery and a venture capital firm.[101][103] Following the release of the 2024 filings, Omar tweeted in February 2025 that she is barely worth “thousands let alone millions”.[104][105][106]

Political positions

| Part of a series on |

| Progressivism in the United States |

|---|

|

Education

Omar supports broader access to student loan forgiveness programs, as well as free tuition for college students whose family income is below $125,000.[107] Omar supports Bernie Sanders‘s plan to eliminate all $1.6 trillion in outstanding student debt, funded by an 0.5% tax on stock transactions and a 0.1% tax on bond transactions;[108] she introduced a companion bill in the House of Representatives.[109] In June 2019, Omar and Senator Tina Smith introduced the No Shame at School Act, which would end the marking of—and punishment for—students with school meal debt.[110]

Health care

Omar supports Medicare for All as proposed in the Expanded and Improved Medicare for All Act.[21][111]

On July 19, 2022, after the Supreme Court overruled Roe v. Wade in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Omar and 17 other members of Congress were arrested in an act of civil disobedience for refusing to clear a street during a protest for reproductive rights outside the Supreme Court Building.[112][113]

Foreign affairs

Omar has criticized Saudi Arabia‘s human rights abuses and the Saudi-led intervention in the Yemeni civil war.[114][115] In October 2018, she tweeted: “The Saudi government might have been strategic at covering up the daily atrocities carried out against minorities, women, activists and even the #YemenGenocide, but the murder of Jamal Khashoggi should be the last evil act they are allowed to commit.”[115] She also called for a boycott of Saudi Arabia’s regime, tweeting: “#BDSSaudi.”[116] The Saudi Arabian government responded by having dozens of anonymous Twitter troll accounts it controlled post tweets critical of Omar.[114]

Omar condemned China‘s treatment of its ethnic Uyghur people.[117] In a Washington Post op-ed, Omar wrote, “Our criticisms of oppression and regional instability caused by Iran are not legitimate if we do not hold Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain to the same standards. And we cannot continue to turn a blind eye to repression in Saudi Arabia—a country that is consistently ranked among the worst of the worst human rights offenders.”[118] She also condemned the Assad regime in Syria.[119] Omar criticized Trump’s decision to impose further sanctions on Iran, saying the sanctions devastated the “country’s middle class and increased hostility toward the United States, with tensions between the two countries rising to dangerous levels.”[120]

Omar opposed the October 2019 Turkish offensive into north-eastern Syria, writing, “What has happened after Turkey’s invasion of northeastern Syria is a disaster—tens of thousands of civilians have been forced to flee, hundreds of Islamic State fighters have escaped, and Turkish-backed rebels have been credibly accused of atrocities against the Kurds.”[120]

In October 2019, Omar voted “present” on H.Res. 296, to recognize the Armenian genocide,[121] causing a backlash.[122][123] She said in a statement that “accountability and recognition of genocide should not be used as cudgel in a political fight” and argued that such a step should include both the Atlantic slave trade and the Native American genocide.[124] In November, after her controversial vote, Omar publicly condemned the Armenian genocide at a rally for presidential candidate Bernie Sanders.[125][126]

In September 2025, Omar introduced a war powers resolution to prevent the Trump administration from conducting future strikes in the Caribbean following a US attack on a Venezuelan boat.[127]

Immigration

In a March 2019 Politico interview, Omar criticized Barack Obama‘s “caging of kids” along the Mexican border.[128][129] Omar accused Politico of distorting her comments and said that she had been “saying how [President] Trump is different from Obama, and why we should focus on policy not politics,” adding, “One is human, the other is really not.”[130]

In June 2019, Omar was one of four Democratic representatives to vote against the Emergency Supplemental Appropriations for Humanitarian Assistance and Security at the Southern Border Act, a $4.5 billion border funding bill that required Customs and Border Protection to enact health standards for individuals in custody such as standards for “medical emergencies; nutrition, hygiene, and facilities; and personnel training.” “Throwing more money at the very organizations committing human rights abuses—and the very Administration directing these human rights abuses—is not a solution. This is a humanitarian crisis … inflicted by our own leadership,” she said.[131][132]

Infrastructure spending

On November 5, 2021, Omar was one of six House Democrats to break with their party and vote against the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act because it was decoupled from the social safety net provisions in the Build Back Better Act.[133][134]

Israeli–Palestinian conflict

Support for boycott efforts and other criticisms

While she was in the Minnesota legislature, Omar was critical of the Israeli government and opposed a law prohibiting the state from working with companies that support the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement.[135] She compared the movement to people who “engage[d] in boycotts” of apartheid in South Africa.[116] During her House campaign, she said she did not support the BDS movement, describing it as counterproductive to peace.[136][137] After the election her position changed, as her campaign office told Muslim Girl that she supports the BDS movement despite “reservations on the effectiveness of the movement in accomplishing a lasting solution.”[138][139][136] Omar has voiced support for a two-state solution to resolve the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[116][118] She criticized Israel’s settlement building in the Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories in the West Bank.[140]

In 2018, Omar came under criticism for statements she made about Israel before she was in the Minnesota legislature.[135][137] In a 2012 tweet, she wrote, “Israel has hypnotized the world, may Allah awaken the people and help them see the evil doings of Israel.”[135][141] The comment, particularly that Israel had “hypnotized the world”, was criticized as drawing on antisemitic tropes.[135] Then-The New York Times columnist Bari Weiss wrote that Omar’s statement tied into a millennia-old “conspiracy theory of the Jew as the hypnotic conspirator”.[142] When asked in an interview how she would respond to American Jews who found the remark offensive, Omar replied: “I don’t know how my comments would be offensive to Jewish Americans. My comments precisely are addressing what was happening during the Gaza War and I’m clearly speaking about the way the Israeli regime was conducting itself in that war.”[141] After reading Weiss’s commentary, Omar apologized for not “disavowing the anti-Semitic trope I unknowingly used”.[143]

In September 2019, Omar condemned Benjamin Netanyahu‘s plans to annex the eastern portion of the occupied West Bank known as the Jordan Valley.[144] Omar said Israelis should not vote for Netanyahu in the September 2019 Israeli legislative election.[145]

Remarks on AIPAC and American support for Israel

In February 2019, Republican House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy threatened to “take action” against Omar and Rashida Tlaib for their support of the BDS movement. When journalist Glenn Greenwald responded that it was remarkable “how much time U.S. political leaders spend defending a foreign nation even if it means attacking free speech rights of Americans”, and tagged Omar for a comment, she replied with a quote from a hip hop song, “It’s All About the Benjamins“, alluding to a slang term for U.S. $100 bills. Both Democratic and Republican politicians accused her of using an antisemitic trope regarding Jews and money, although some Democratic politicians defended Omar’s comment. Omar later said that she was referring to the influence of pro-Israel lobbyists in the United States, especially AIPAC.[146][147]

A number of Democratic leaders—including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, and Majority Whip Jim Clyburn—condemned the tweet, which was interpreted as implying that money was fueling American politicians’ support of Israel.[148] The Democratic House leadership released a statement accusing Omar of “engaging in deeply offensive anti-Semitic tropes”.[149] The Jewish Democratic Council of America (JDCA) also denounced her statements.[150] Omar issued an apology the next day, saying, “I am grateful for Jewish allies and colleagues who are educating me on the painful history of anti-Semitic tropes”, and adding, “I reaffirm the problematic role of lobbyists in our politics, whether it be AIPAC, the NRA or the fossil fuel industry.”[149] The Anti-Defamation League accused her of promoting an “ugly conspiracy theory” about Jewish influence in politics.[151] Journalist Peter Beinart, after tweeting that the controversy was about “policing the American debate over Israel”,[152] thought Omar’s statement inaccurate, wrong and irresponsible, but argued that her congressional critics were more “bigoted” on Israeli-Palestinian issues than Omar.[153]

On February 27, 2019, Omar said of her critics: “I want to talk about the political influence in this country that says it is OK for people to push for allegiance to a foreign country.” The statements were quickly criticized as allegedly drawing on antisemitic tropes. House Foreign Affairs Committee chairman Eliot Engel said it was “deeply offensive to call into question the loyalty of fellow American citizens” and asked Omar to retract her statement.[154] House Appropriations Committee chairwoman Nita Lowey also called for an apology and criticized the statements in a March 3 tweet, which led to an online exchange between the two. In response, Omar reaffirmed her position, insisting that she “should not be expected to have allegiance/pledge support to a foreign country in order to serve my country in Congress or serve on committee.”[155][156] Omar said she was simply criticizing Israel, drawing a distinction between criticism of Benjamin Netanyahu and being anti-Semitic.[157][158] Omar’s spokesman, Jeremy Slevin, said Omar was speaking out about “the undue influence of lobbying groups for foreign interests.”[159]

Reaction among 2020 Democratic presidential candidates was mixed. Senators Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, and Bernie Sanders defended Omar.[160] While Senator Cory Booker found her comments “disturbing”, he recognized that some of the attacks against her had “anti-Islamic sentiment”. Kirsten Gillibrand said, “those with critical views of Israel should be able to express their views without employing anti-Semitic tropes about money or influence”, but also criticized the Republican Party for censuring Omar while saying “little or nothing” when President Trump “defended white supremacists at Charlottesville.” New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio called Omar’s remarks “unacceptable”.[161][162] According to The Guardian, election records archived by OpenSecrets “suggest a correlation between pro-Israel lobby campaign contributions and Democratic presidential candidates’ position on the controversy.”[163] Some members of the Congressional Black Caucus believed Omar was unfairly targeted because she is a black Muslim, saying that “the Democratic leadership did not draft a resolution condemning Donald Trump or other white male Republicans over their antisemitic remarks.”[163] The second round of remarks prompted the Democratic leadership to introduce a resolution condemning antisemitism that did not specifically refer to Omar. After objections by a number of congressional progressive Democrats, the resolution was amended to include Islamophobia, racism, and homophobia.[164] On March 7, the House passed the amended resolution. Omar called the resolution “historic on many fronts” and said, “We are tremendously proud to be part of a body that has put forth a condemnation of all forms of bigotry including anti-Semitism, racism, and white supremacy.”[165] Some Minnesota Jewish and Muslim community leaders later expressed continuing concern about Omar’s statements and indicated that the issue remained divisive in Omar’s district.[166]

On March 7, 2019, the U.S. House of Representatives voted 407–23 to condemn “anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, racism and other forms of bigotry” in response to Omar’s remarks concerning Israel.[167] On February 2, 2023, the Republican-led House of Representatives passed a resolution, on a party-line vote, to remove Omar from the House Foreign Affairs Committee for what Speaker Kevin McCarthy called “repeated antisemitic and anti-American remarks.”[168][169] Many prominent House Democrats stood by Omar.[170] On July 18, 2023, she voted against a congressional non-binding resolution proposed by August Pfluger, which states that “the State of Israel is not a racist or apartheid state“, that Congress rejects “all forms of antisemitism and xenophobia”, and that “the United States will always be a staunch partner and supporter of Israel”.[171] On October 16, 2023, Omar signed a resolution calling for a ceasefire in the Gaza war. She criticized the United States’ support for Israeli bombing of the Gaza Strip.[172] In May 2024, Omar voiced support for the International Criminal Court investigation in Palestine, saying that the ICC “must be allowed to conduct its work independently and without interference.”[173][174] In August 2024, she criticized the Biden administration’s arms shipments to Israel, saying that “if you really want a ceasefire, you just stop sending the weapons.”[175]

Ban from entering Israel

In August 2019, Omar and Representative Rashida Tlaib were banned from entering Israel, a reversal from the July 2019 statement by Israeli Ambassador to the United States Ron Dermer that “any member of Congress” would be allowed in. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu attributed the ban to Israeli law preventing the entry of people who call for a boycott of Israel (as Omar and Tlaib had done with their support for BDS). Netanyahu also cited Omar and Tlaib listing their destination as Palestine instead of Israel, claiming he thus viewed their visit as an attempt to “hurt Israel and increase its unrest”. Netanyahu also said that Omar and Tlaib did not plan on visiting or meeting with any Israeli officials from the government or the opposition, and additionally accused Miftah, the sponsor of Omar’s trip, of having members who support terrorism against Israel (in 2016, Israel approved a visit by five U.S. representatives to Israel that Miftah co-sponsored, but that was before Israel enacted its anti-BDS law).[176][177] Less than two hours before the ban, President Trump tweeted that Israel allowing the visit would “show great weakness” when Omar and Tlaib “hate Israel & all Jewish people”.[178][179][180][176] Omar said that Netanyahu had caved to Trump’s demand and that “Trump’s Muslim ban is what Israel is implementing”. She responded to Netanyahu that she had intended to meet members of Israel’s legislative Knesset and Israeli security officials. Both Democratic and Republican legislators criticized the ban and requested that Israel rescind it.[181][182] AIPAC released a statement saying that it disagreed with Israel’s move and that Omar and Tlaib should have been allowed to “experience Israel firsthand”, while the head of the American Jewish Committee put out a statement agreeing with AIPAC on the matter.[183] U.S. Representative Max Rose also criticized the move to ban Omar, saying that Omar and Tlaib did not speak for the Democratic Party.[184]

LGBT rights

In March 2019, Omar addressed a rally in support of a Minnesota bill that would ban gay conversion therapy in the state. She co-sponsored a similar bill when she was a member of the Minnesota House.[185] In May 2019, Omar introduced legislation that would sanction Brunei over a recently introduced law that would make homosexual sex and adultery punishable by death.[186] In June 2019, she participated in Twin Cities Pride in Minnesota.[187] In August 2019, Omar wrote on Twitter in support of the Palestinian LGBT rights group Al Qaws after the Palestinian Authority banned Al Qaws’s activities in the West Bank.[188][189]

Military policy

Omar has been critical of U.S. foreign policy, and has called for reduced funding for “perpetual war and military aggression”,[190] saying, “knowing my tax dollars pay for bombs killing children in Yemen makes my heart break,” with “everyone in Washington saying we don’t have enough money in the budget for universal health care, we don’t have enough money in the budget to guarantee college education for everyone.”[190] Omar has criticized the U.S. government’s drone assassination program, citing the Obama administration’s policy of “droning of countries around the world”.[128][129] She has said, “we don’t need nearly 800 military bases outside the United States to keep our country safe.”[118]

In 2019, Omar signed a letter led by Representative Ro Khanna and Senator Rand Paul to President Trump asserting that it is “long past time to rein in the use of force that goes beyond congressional authorization” and that they hoped this would “serve as a model for ending hostilities in the future—in particular, as you and your administration seek a political solution to our involvement in Afghanistan.”[191][192]

In May 2020, Omar signed a letter backed by AIPAC calling for the continuation of the UN embargo against Iran,[193] with her office noting that it was a “narrow ask that we couldn’t find anything wrong with.” Her office said that she has opposed human rights abuse “for a long time” and that signing onto it should be not be seen as a sign she supports the Trump administration’s policy on Iran.[194]

On July 6, 2023, President Biden authorized the provision of cluster munitions to Ukraine in support of a Ukrainian counter-offensive against Russian forces in Russian-occupied southeastern Ukraine.[195] Omar opposed the decision, saying, “We can support the people of Ukraine in their freedom struggle while also opposing violations of international law.”[196]

Minimum wage

In 2017, Omar supported a $15 hourly minimum wage.[21][197] In 2023, she introduced a bill that would raise the minimum wage to $17 by 2028.[198]

Minneapolis Police Department

In June 2020, the “defund the police” slogan gained widespread popularity following the murder of George Floyd. Black Lives Matter and other activists used the phrase to call for police budget reductions and a plan to delegate certain police responsibilities to other organizations. Reacting to the murder of Floyd, the majority of the Minneapolis City Council voted to dismantle the city’s police department. In a statement, the Minneapolis mayor said they planned to work to address “systemic racism in police culture”.[199][200] Following the murder of Floyd, Omar supported the police abolition movement in Minneapolis that sought to dismantle the Minneapolis Police Department, saying that the department had “proven themselves beyond reform.”[200] Omar hoped to see a new police department that would be modeled after the Camden County Police Department in New Jersey.[citation needed]

TikTok

Omar has opposed a TikTok ban.[201] In March 2024, she raised First Amendment concerns in opposing a bill that would ban the app if its Chinese owner did not sell, saying: “We should create actual standards & regulations around privacy violations across social media companies—not target platforms we don’t like.”[202]

On March 12, Omar was asked about TikTok-related national security concerns, such as China using the app to ramp up divisions in the U.S., and replied, “We had an intel briefing, and none of the information that was provided to us really was persuasive in the fact that there is anything to be really concerned”, adding, “for the first time in our nation’s history, Americans have access to real images [through TikTok] of the horrors that are experienced by Palestinians daily.”[203][204]

Venezuela crisis

In January 2019, amid the Venezuelan presidential crisis, Omar joined Democrats Ro Khanna and Tulsi Gabbard in denouncing the Trump administration’s decision to recognize Juan Guaidó, the president of the Venezuelan National Assembly, as Venezuela’s interim president.[205] She described Trump’s action as a “U.S. backed coup” and said that the U.S. should not “hand pick” foreign leaders[206] and should support “Mexico, Uruguay & the Vatican’s efforts to facilitate a peaceful dialogue.”[205] In response to criticisms of her comments, Omar wrote that “No one is defending Maduro” and that opposing US intervention is not the equivalent of supporting the existing leadership of a country.[207]

In February 2019, Omar questioned whether Elliott Abrams, whom Trump appointed as Special Representative for Venezuela in January 2019, was the correct choice given his past support of right-wing authoritarian regimes in El Salvador and Guatemala, his initial doubts about the number of reported deaths in the El Mozote massacre in 1982, and his two 1991 misdemeanor convictions for withholding information from Congress about the Iran–Contra affair, for which he was later pardoned by George H. W. Bush.[208][209]

In May 2019, Omar said in an interview on Democracy Now! that she believed U.S. foreign policy and economic sanctions are aimed at regime change and have contributed to the “devastation in Venezuela”.[210]

Death threats and harassment

DFL caucus attack

On February 4, 2014, Omar was attacked and injured by multiple attendees during a DFL caucus for Minnesota’s House of Representatives District 60B.[211] She was organizing the event and was a policy aide to Minneapolis City Councilman Andrew Johnson at the time. She sustained a concussion and was sent to the hospital.[212]

Death threats

In February 2019, the FBI arrested United States Coast Guard Lieutenant Christopher Paul Hasson, who was allegedly plotting to assassinate various journalists and political figures in the United States, including Omar. According to prosecutors, Hasson is a self-described “long time White Nationalist” and former skinhead who wanted to use violence to “establish a white homeland.” Prosecutors also alleged that Hasson was in contact with an American neo-Nazi leader, stockpiled weapons, and compiled a hit list.[213]

On April 7, 2019, Patrick Carlineo Jr., was arrested for threatening to assault and murder Omar in a phone call to her office. He reportedly told investigators that he did not want Muslims in the government.[214][215] In May 2019, Carlineo was released from custody and placed on house arrest.[216] He pleaded guilty to the offense on November 19.[217] Omar asked the court to be lenient with him.[218]

In April 2019, Omar said that she had received more death threats after Trump made comments about her and 9/11, “many directly referencing or replying to the president’s video”.[219] In August 2019, she published an anonymous threat she had received of being shot at the Minnesota State Fair, saying that such threats were why she now had security protection.[220] In September 2019, she asserted Trump was putting her life in danger by retweeting a tweet falsely claiming she had “partied on the anniversary of 9/11”.[221]

Two Republican candidates for congressional office have called for Omar’s execution.[222] In November 2019, Danielle Stella, Omar’s Republican opponent for Congress, was banned from Twitter for suggesting that Omar be hanged for treason if found guilty of passing information to Iran.[217] In December 2019, George Buck, another Republican running for Congress, also suggested that Omar be hanged for treason. In response, Buck was removed from the National Republican Congressional Committee‘s Young Guns program.[223] Neither candidate won their primary election.[224][225]

In January 2026, 60-year-old Adam Lee Osborn of Wichita, Kansas, was arrested following threats he had made against Omar and New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani on social media. In Facebook posts, Osborn had threatened to kill Omar, writing: “If illegals can come here unimpeded, I can kill them unimpeded. How the fuck do I end up a minority in my own country? This shit comes to an end, NOW!” According to an affidavit, during his interrogation, Osborn continued to threaten Omar and Mamdani and said he “wouldn’t mind if they were killed”.[226]

“Go back to their countries” Trump tweet

On July 14, 2019, Trump tweeted that The Squad—a group that consists of Omar and three other young congresswomen of color, most of whom were born and raised in the U.S.—should “go back” to the “places from which they came”.[227][228][229] In response, Omar said Trump was “stoking white nationalism” because he was “angry that people like us are serving in Congress and fighting against your hate-filled agenda.”[229] Two days later, the House of Representatives voted 240–187 to condemn Trump’s “racist comments”.[230] On July 17, it was reported that the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission lists the phrase “Go back to where you came from” as an example of “harassment based on national origin”.[231]

At a July 17 campaign rally in North Carolina, Trump made additional comments about The Squad: “They never have anything good to say. That’s why I say, ‘Hey if you don’t like it, let ’em leave, let ’em leave‘“, and “I think in some cases they hate our country”.[232] He made a series of false and misleading claims about Omar, including allegations that she had praised al-Qaeda and “smeared” American soldiers who had fought in the Battle of Mogadishu by bringing up the numerous Somali civilian casualties.[233][234][235] The crowd reacted by chanting, “Send her back, Send her back.”[236][237] Trump later called the crowd “incredible people, incredible patriots” and accused Omar of racism and antisemitism.[238] On July 19, he falsely claimed that Omar and the rest of The Squad had used the term “evil Jews”.[239]

Foreign media has widely covered Trump’s remarks about Omar and The Squad. The social media hashtag #IStandWithIlhanOmar was soon trending in the United States and other countries.[240] Many foreign politicians condemned Trump’s comments. On July 19, German Chancellor Angela Merkel said, “I reject [Trump’s comments] and stand in solidarity with the congresswomen he targeted.”[240]

Target of online hate speech

Omar has frequently been the target of online hate speech.[241][242] According to a study by the Social Science Research Council of more than 113,000 tweets about Muslim candidates in the weeks leading up to the 2018 midterm elections, Omar “was the prime target. Roughly half of the 90,000 tweets mentioning her included hate speech or Islamophobic or anti-immigrant language.”[243][244] According to the study, “Key themes included Muslims as subhumans or ‘Trojan horses‘ seeking to impose Shariah law on America…. A large proportion of these trolls were likely bots or automated accounts run by people, organizations or state actors seeking to spread political propaganda and hate speech. That’s based on telltale iconography, naming patterns, webs of linkages and the breadth of the postelection scrubbing.”[244]

9/11 comments and World Trade Center cover

On April 11, 2019, the front page of the New York Post carried an image of the World Trade Center burning following the September 11 terrorist attacks and a quotation from a speech Omar gave the previous month. The headline read, “REP. ILHAN OMAR: 9/11 WAS ‘SOME PEOPLE DID SOMETHING‘“, and a caption underneath added, “Here’s your something … 2,977 people dead by terrorism.”[245] The Post was quoting a speech Omar had given at a recent Council on American–Islamic Relations (CAIR) meeting. In the speech Omar said, “CAIR was founded after 9/11 because they recognized that some people did something and that all of us [Muslims in the U.S.] were starting to lose access to our civil liberties.” (CAIR was founded in 1994, but many new members joined after the 9/11 attacks in 2001.)[246][247]

On April 12, President Trump retweeted a video that edited Omar’s remarks to remove context, showing her saying, “Some people did something.”[248][249][250][251] Some Democratic representatives condemned Trump’s retweet, predicting that it would incite violence and hatred. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi called on Trump to “take down his disrespectful and dangerous video” and asked the U.S. Capitol Police to increase its protection of Omar.[252][253]

Speaking at an April 30 protest by black women calling for formal censure of Trump,[254] Omar blamed Trump and his allies for inciting Americans against both Jews and Muslims.[255]

Comments by Lauren Boebert

In November 2021, Republican Representative Lauren Boebert said she had shared an elevator with Omar, and that she and a Capitol Police officer both mistook Omar for a terrorist. Boebert referred to Omar as the “Jihad Squad”.[256] Omar said that she had not shared an elevator with Boebert, that the story was made up, and that Boebert’s comments were “anti-Muslim bigotry”.[257][258]

Spraying incident

During January 2026, federal agents participating in Operation Metro Surge shot three people in Minneapolis, killing two of them. It was announced ahead of time that Omar would hold a town hall meeting in Minneapolis on January 27, the Tuesday after the most recent shooting.[259] During the town hall, a man sprayed apple cider vinegar from a syringe at Omar.[260] Just before being sprayed, Omar had called for the abolition of Immigration and Customs Enforcement[261] and called on Homeland Security secretary Kristi Noem to resign from her position or face impeachment.[262] The man was restrained and whisked out of the room, and Omar continued the town hall.[263][264][265] The incident drew bipartisan condemnation.[266] Hours before Omar was attacked, Trump had criticized her in a speech in Clive, Iowa, saying: “They [immigrants] have to show that they can love our country. They have to be proud, not like Ilhan Omar.” After the town hall attack, Trump accused Omar of staging the incident, saying, “she probably had herself sprayed, knowing her”.[267][268] After the incident, Omar wrote, “this small agitator isn’t going to intimidate me from doing my work” and “I don’t let bullies win”.[268]

Electoral history

2016

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic (DFL) | Ilhan Omar | 2,404 | 40.97 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Mohamud Noor | 1,738 | 29.62 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Phyllis Kahn | 1,726 | 29.41 | |

| Total votes | 5,868 | 100.0 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic (DFL) | Ilhan Omar | 15,860 | 79.77 | |

| Republican | Abdimalik Askar | 3,820 | 19.21 | |

| Write-in | 203 | 1.02 | ||

| Total votes | 19,883 | 100.0 | ||

| Democratic (DFL) hold | ||||

2018

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic (DFL) | Ilhan Omar | 65,238 | 48.2 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Margaret Anderson Kelliher | 41,156 | 30.4 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Patricia Torres Ray | 17,629 | 13.0 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Jamal Abdulahi | 4,984 | 3.7 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Bobby Joe Champion | 3,831 | 2.8 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Frank Drake | 2,480 | 1.8 | |

| Total votes | 135,318 | 100.0 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic (DFL) | Ilhan Omar | 267,703 | 77.97 | |

| Republican | Jennifer Zielinski | 74,440 | 21.68 | |

| Write-in | 1,215 | 0.35 | ||

| Total votes | 343,358 | 100.0 | ||

| Democratic (DFL) hold | ||||

2020

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic (DFL) | Ilhan Omar | 92,443 | 57.4 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Antone Melton-Meaux | 63,059 | 39.2 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | John Mason | 2,497 | 1.6 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Daniel Patrick McCarthy | 1,792 | 1.1 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Les Lester | 1,147 | 0.7 | |

| Total votes | 160,938 | 100.0 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic (DFL) | Ilhan Omar | 255,924 | 64.3 | |

| Republican | Lacy Johnson | 102,878 | 25.8 | |

| Legal Marijuana Now | Michael Moore | 37,979 | 9.5 | |

| Green | Toya Woodland | 34 | 0.0 | |

| Total votes | 398,263 | 100.0 | ||

| Democratic (DFL) hold | ||||

2022

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic (DFL) | Ilhan Omar | 57,683 | 50.3 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Don Samuels | 55,217 | 48.2 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Nate Schluter | 671 | 0.6 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | AJ Kern | 519 | 0.5 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Albert Ross | 477 | 0.4 | |

| Total votes | 114,567 | 100.0 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic (DFL) | Ilhan Omar (incumbent) | 214,224 | 74.3 | |

| Republican | Cicely Davis | 70,702 | 24.5 | |

| Write-in | 3,280 | 1.1 | ||

| Total votes | 288,206 | 100.0 | ||

| Democratic (DFL) hold | ||||

2024

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic (DFL) | Ilhan Omar (incumbent) | 67,926 | 56.2 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Don Samuels | 51,839 | 42.9 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Nate Schluter | 575 | 0.5 | |

| Democratic (DFL) | Abena McKenzie | 461 | 0.4 | |

| Total votes | 120,801 | 100.0 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic (DFL) | Ilhan Omar (incumbent) | 261,066 | 74.4 | |

| Republican | Dalia Al-Aqidi | 86,213 | 24.6 | |

| Write-in | 3,768 | 1.1 | ||

| Total votes | 351,047 | 100.0 | ||

| Democratic (DFL) hold | ||||

Awards and honors

Omar received the 2015 Community Leadership Award from Mshale, an African immigrant media outlet based in Minneapolis. The prize is awarded annually on a readership basis.[278]

In 2017, Time magazine named Omar among its “Firsts: Women who are changing the world,” a special report on 46 women who broke barriers in their respective disciplines, and featured her on the cover of its September 18 issue.[279] Her family was named one of the “five families who are changing the world as we know it” by Vogue in their February 2018 issue featuring photographs by Annie Leibovitz.[280]

Media appearances

In 2018, Omar was featured in the music video for Maroon 5‘s “Girls Like You” featuring Cardi B.[281]

The 2018 documentary film Time for Ilhan (directed by Norah Shapiro, produced by Jennifer Steinman Sternin and Chris Newberry) chronicles Omar’s political campaign.[282] It was selected to show at the Tribeca Film Festival and the Mill Valley Film Festival.[283][284]

Following a July 2019 tweet by Trump that The Squad—a group that consists of Omar and three other congresswomen of color who were born in the United States—should “go back” to the “places from which they came”,[227] Omar and the other members of the Squad held a press conference that was taped by CNN and posted to social media.

[285]

On October 19, 2020, Omar joined Ocasio-Cortez, Disguised Toast, Jacksepticeye, and Pokimane in a Twitch stream playing the popular game Among Us, encouraging streamers to vote in the 2020 election. This collaboration garnered almost half a million views.[286]

Personal life

In 2002, Omar became engaged to Ahmed Abdisalan Hirsi (né Aden). She has said they had an unofficial, faith-based Islamic marriage.[287] The couple had two children together,[55][288] including Isra Hirsi, one of the three principal organizers of the school strike for climate in the US.[289] Omar has said that she and Hirsi divorced within their faith tradition in 2008.[55][288]

In 2009, Omar married Ahmed Nur Said Elmi, a British Somali.[55] According to Omar, in 2011 she and Elmi had a faith-based divorce and she reconciled with Hirsi, with whom she had a third child in 2012.[290][55] In 2017, Elmi and Omar legally divorced,[50] and Omar and Hirsi legally married in 2018.[31] On October 7, 2019, Omar filed for divorce from Hirsi, citing an “irretrievable breakdown” of the marriage.[291] The divorce was finalized on November 5, 2019.[288][292]

In March 2020, Omar married Tim Mynett, a political consultant whose political consulting firm, the E Street Group, received $2.78 million in contracts from Omar’s campaign during the 2020 cycle.[293][294][295] The campaign’s contract with Mynett’s firm became a focus of criticism by her Democratic primary opponent and conservative critics that received significant local and national media attention.[296][297] On November 17, 2020, Omar’s campaign terminated its contract with Mynett’s firm, saying the termination was to “make sure that anybody who is supporting our campaign with their time or financial support feels there is no perceived issue with that support”.[298]

In 2020, HarperCollins published Omar’s memoir, This Is What America Looks Like, written with Rebecca Paley.[299]

See also

- List of African-American United States representatives

- List of Muslim members of the United States Congress

- Women in the United States House of Representatives

Notes

- ^ Omar has stated that she and Elmi had a faith-based divorce in 2011, and remained legally married until 2017.

- ^ Omar has stated that she and Hirsi had a faith-based marriage in 2002 and a faith-based divorce in 2008, before reconciling in 2012 and getting legally married in 2018. Their divorce was finalized on November 5, 2019.

- ^ Recorded November 17, 2022

References

- ^ Ilhan Omar [@IlhanMN] (October 17, 2020). “#MyNameIs Ilham, I prefer Ilhan. I never liked the M sound. It means “Inspiration” in Arabic. My father named me Ilham and inspired me to lead a life of service to others. In his honor I am voting for an inspirational ticket over desperate and maddening one” (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Stolberg, Sheryl Gay (April 16, 2019). “For Democrats, Ilhan Omar Is a Complicated Figure to Defend”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- ^ Kotch, Alex (February 13, 2019). “Ilhan Omar is right about the influence of the Israel lobby”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 24, 2019. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- ^ Sasley, Brent (February 12, 2019). “What the controversy over Ilhan Omar’s tweets tells us about AIPAC today”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 25, 2019. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- ^ Schapitl, Lexie (February 2, 2023). “House Republicans vote to remove Rep. Ilhan Omar from the Foreign Affairs Committee”. NPR. Archived from the original on June 12, 2023. Retrieved August 6, 2023.

- ^ Golden, Erin (November 7, 2018). “Ilhan Omar makes history, becoming first Somali-American elected to U.S. House”. Star Tribune. Minneapolis, Minn. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019.

- ^ a b O’Grady, Siobhán (November 7, 2018). “Trump demonized Somali refugees in Minnesota. One of them just won a seat in Congress”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 4, 2019.

- ^ “NDSU Fall 2011 Graduates” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 28, 2018.

- ^ Gessen, Masha (April 15, 2019). “The Dangerous Bullying of Ilhan Omar”. The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 23, 2019. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- ^ “Ilhan Omar reveals racist threat to shoot her at state fair”. BBC News. August 29, 2019. Archived from the original on December 2, 2019. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- ^ United States Congress. “Ilhan Omar (id: O000173)”. Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ^ a b c Montemayor, Stephen (October 27, 2018). “On the edge of making history, Ilhan Omar confronts fresh wave of scrutiny”. Star Tribune. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on October 1, 2023. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- ^ Reinl, James (November 15, 2016). “Ilhan Omar: First female Somali American lawmaker”. Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on March 8, 2019.

- ^ Omar, Ilhan (June 16, 2016). “Questions from a 5th grader”. Neighbors for Ilhan. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017.

- ^ “Ilhan Omar & Her Journey”. Tablet Magazine. July 21, 2022. Retrieved April 17, 2025.

- ^ Marlowe, Ann (March 22, 2019). “We Should Be Paying More Attention to Somalia”. The Bulwark. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- ^ Hirsi, Ibrahim (June 20, 2020). “‘He was loved by everyone’: Somali community remembers Nur Omar Mohamed, who died of COVID-19″. Sahan Journal. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c Zurowski, Cory (November 7, 2016). “Ilhan Omar’s improbable journey from refugee camp to Minnesota Legislature”. City Pages. Minneapolis: Star Tribune Media Company. Archived from the original on March 7, 2019.

- ^ Yimer, Solomon (November 7, 2018). “Ilhan Omar Just Became the First Muslim Women Elected to US Congress”. ethio.news. news.et. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- ^ Iqbal, Zainab (February 4, 2019). “Ilhan Omar On Being Unapologetically Muslim”. Archived from the original on February 16, 2019. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Stolberg, Sheryl Gay (December 30, 2018). “Glorified and Vilified, Representative-Elect Ilhan Omar Tells Critics: ‘Just Deal’“. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ Adam, Anita Sylvia. “Benadiri People of Somalia” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 1, 2019. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ Nichols, John (May 21, 2019). “Ilhan Omar: ‘There’s a Reason That I Got Elected to Be in Congress, and It Has Nothing to Do With the Fact That I’m a Refugee’“. The Nation. Archived from the original on April 20, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ a b Holpuch, Amanda (February 29, 2016). “‘This is my country’: Muslim candidate aims to break boundaries in Minnesota”. The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019.

- ^ Schaub, Michael (January 19, 2019). “Rep. Ilhan Omar, Somali refugee turned congresswoman, to publish memoir in 2020”. LA Times. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

…in Somalia, which she left as a child with her family after the outbreak of the Somali civil war.

- ^ “Ilhan Omar elected first Somali-American legislator in the US”. Al Arabiya English. November 9, 2016. Archived from the original on July 9, 2018.

- ^ Bhalla, Nita (November 7, 2018). “Ex-Somali refugee’s U.S. Congress win sparks debate in former home Kenya”. Reuters. Archived from the original on November 7, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ Jaffe, Greg; Mekhennet, Souad (July 6, 2019). “Ilhan Omar’s American story: It’s complicated”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 2, 2019. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Luckhurst, Toby (February 15, 2019). “Ilhan Omar: Who is Minnesota’s Somalia-born congresswoman?”. BBC News. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Omar, Mahamad (November 1, 2016). “From Refugee to St. House Race, Ilhan Omar Looks to Break New Ground”. Arab American Institute. Archived from the original on November 14, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Forliti, Amy (October 17, 2018). “Minnesota House hopeful calls marriage, fraud claims ‘lies’“. AP News. Archived from the original on March 11, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ Duarte, Lorena (October 21, 2015). “‘Done Wishing’: Ilhan Omar on why she’s running for House District 60B”. MinnPost. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on March 20, 2019. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ “Excerpts”. NDSU Magazine. Vol. 14, no. 1. North Dakota State University. Winter 2017. Archived from the original on July 8, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- ^ a b c “Ilhan’s Story”. Neighbors for Ilhan. Archived from the original on November 6, 2016.

- ^ “Omar, Ilhan”. Minnesota Legislative Reference Library. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- ^ “Editorial: The Minnesota Daily’s endorsement for Minnesota’s 5th Congressional District”. The Minnesota Daily. October 31, 2018. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- ^ Rosen, Armin (April 10, 2019). “As Keith Ellison Leaves Congress, One Likely Replacement Faces Criticism for Anti-Israel Views”. Tablet. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ Nord, James; Bierschbach, Briana (February 18, 2014). “Allegations of threats, bullying follow Cedar-Riverside caucus brawl”. MinnPost. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on May 1, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ Cirillo, Jeff (August 13, 2018). “Abuse Allegations Loom Over Minnesota Race to Replace Ellison”. Roll Call. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ^ Coolican, J. Patrick; Klecker, Mara (August 10, 2016). “Ilhan Omar makes history with victory over long-serving Rep. Phyllis Kahn”. Star Tribune. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ Sawyer, Liz (August 27, 2016). “GOP state House candidate to suspend campaign against Ilhan Omar”. Star Tribune. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ Blair, Olivia (November 9, 2016). “Ilhan Omar: Former refugee is elected as America’s first Somali American Muslim woman legislator”. The Independent. London. Archived from the original on September 28, 2018.

- ^ Lopez, Ricardo (January 4, 2017). “Dayton, legislators kick off session in newly refurbished Capitol”. Star Tribune. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on September 27, 2018. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ Achterling, Michael (January 22, 2018). “Rep. Ilhan Omar launches re-election bid ahead of second legislative session”. The Minnesota Daily. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- ^ Pugmire, Tim (December 14, 2016). “Omar lands DFL leadership post before taking office”. Capitol View. Archived from the original on February 21, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ “Office of the Revisor of Statutes: Search Results”. revisor.mn.gov. Minnesota Legislature. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ Perry, David (October 15, 2019). “Why Ilhan Omar Is the Optimist in the Room”. The Nation. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- ^ “Ilhan Omar (DFL) 60B – Minnesota House of Representatives”. house.leg.state.mn.us. Archived from the original on November 10, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- ^ Bierschbach, Briana (July 30, 2018). “Drazkowski: Omar’s speaking fees violate House policy”. Minnesota Public Radio Capitol View. Archived from the original on December 7, 2018. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- ^ a b Van Berkel, Jessie (July 24, 2018). “Fellow legislator accuses Ilhan Omar of using campaign funds for divorce lawyer”. The Minnesota Star Tribune. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on April 6, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2025.

- ^ “Minnesota lawmaker questions Omar’s campaign spending”. AP News. October 10, 2018. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ “Ilhan Omar violated Minnesota campaign finance rules, state officials say”. Times of Israel. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Archived from the original on June 9, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ “Ilhan Omar To Repay Thousands Amid Controversy Over Personal Tax Returns”. CBS News. June 10, 2019. Archived from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved December 14, 2025.

- ^ Greenwood, Max (June 11, 2019). “Omar’s joint tax filings draw scrutiny”. The Hill. Archived from the original on December 13, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Forliti, Amy (June 12, 2019). “Rep. Omar filed joint tax returns before she married husband”. AP News. Archived from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved December 14, 2025.

- ^ Potter, Kyle (June 5, 2018). “Nation’s 1st Somali-American lawmaker eyes seat in Congress”. AP News. Archived from the original on January 9, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Golden, Erin (June 18, 2018). “DFL endorses Omar for Ellison’s congressional seat”. Star Tribune. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on September 20, 2018. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ “Minnesota Primary Election Results”. The New York Times. August 16, 2018. Archived from the original on April 29, 2019. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- ^ “Ilhan Omar, Jennifer Zielinski win primary for Minnesota’s 5th District”. FOX 9. Minneapolis, Minn.: KMSP-TV. August 14, 2018. Archived from the original on October 21, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ Magane, Azmia (November 9, 2018). “Congresswoman-Elect Ilhan Omar Shares Advice for Young People and How She Deals With Islamophobia”. Teen Vogue. Archived from the original on February 18, 2019. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ Newburger, Emma (August 15, 2018). “Two Democrats are poised to become the first Muslim women in Congress”. CNBC. Archived from the original on May 9, 2019. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ “Ilhan Omar: Reaction to first Somali-American elected to Congress”. BBC News. November 7, 2018. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ a b Ostermeier, Eric (November 13, 2018). “Ilhan Omar nearly breaks Minnesota U.S. House electoral record”. Smart Politics. Archived from the original on March 13, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ Herrera, Jack (January 4, 2019). “Using a Quran to Swear in to Congress: A Brief History of Oaths and Texts”. Pacific Standard. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ Karas, Tania (January 3, 2019). “Two reps were sworn in on the Quran. It’s a symbolic moment for Muslim Americans”. Public Radio International. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ Bowden, Ebony (July 20, 2020). “‘Squad’ members Rashida Tlaib, Ilhan Omar facing tough primary challenges”. New York Post. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Herndon, Astead W. (August 11, 2020). “Ilhan Omar Wins House Primary in Minnesota”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 12, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Wulfsohn, Joseph (July 20, 2020). “Minneapolis Star Tribune backs Omar’s primary challenger, call out ‘Squad’ member’s ‘ethical distractions’“. Foxnews. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ Mutnick, Ally; Montellaro, Zach (August 11, 2020). “Ilhan Omar’s career on the line in tough primary”. Politico. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ “Minnesota’s Ilhan Omar easily wins against well-funded challenger”. Al Jazeera. August 12, 2020. Archived from the original on August 12, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Christopher (August 12, 2020). “Omar easily wins primary challenge as ‘the Squad’ continues unbeaten streak”. Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on August 12, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ “Results for All Congressional Districts”. Minnesota Secretary of State. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Rakich, Nathaniel (March 23, 2021). “The Strongest House Candidates In 2020 Were (Mostly) Moderate”. FiveThirtyEight. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ Bradner, Eric (August 9, 2022). “Omar survives surprising nail-biter to win Democratic nomination for Minnesota’s 5th Congressional District, CNN projects”. CNN. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ a b Weigel, Dave (August 9, 2022). “Rep. Ilhan Omar survives close primary after campaign focused on policing”. Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ “Minnesota House District 5 Democratic Primary Election Results and Maps 2022”. CNN. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ Weisman, Jonathan; Kelly, Kate (December 15, 2023). “Democratic Critics of Israel Draw Challengers Eyeing AIPAC’s Help”. The New York Times.

- ^ Cowan, Richard (August 14, 2024). “Ilhan Omar wins Democratic nomination, boosts US House liberals”. Reuters. Retrieved February 19, 2025.